Definitions

Since this article discusses software in various forms, we need to define a few terms:

- Source code

- Computer commands written by a programmer in one or more of many computer languages. Computer languages are classified as either compiled or interpreted.

- Interpreted language

- A programming language that executes source code directly, without compiling the source code.

- Compiled language

- A programming language that translates source code into executable object code.

- Object code

- The executable (ready-to-run) program resulting from compiling source code. Only compiled languages save the generated object code; interpreted languages generally do not produce object code.

- Decompile

- Reconstitute source code from object code. Decompilation is the opposite of compilation.

- Reverse engineer

- To take something apart to see how it works, to duplicate or enhance it. When a technology expert reverse-engineers a product for legal purposes the results cannot be used to create a competing product or be publicly shared.

As a software expert, I am able to work with source code and object code, and decompile or reverse-engineer software when necessary. I have also opined on whether a party’s software was copied verbatim, translated or otherwise derived from another party’s software.

Copying is Binary

One defendant’s expert, whose opinions I rebutted, had suggested that the defendant’s copying was insignificant and should be disregarded since only a few thousand lines of code had been translated, amounting to a small percentage of the total amount of the defendant’s code. Just as one cannot be just a little bit pregnant, copying is a binary state; either copying occurred, or it did not.

Once I believe that copying occurred, my job is to quantify the degree of certainty of my opinion. Computing the confidence factor, and communicating it effectively, is an important part of my task as an expert.

Inspecting Compiled Programs

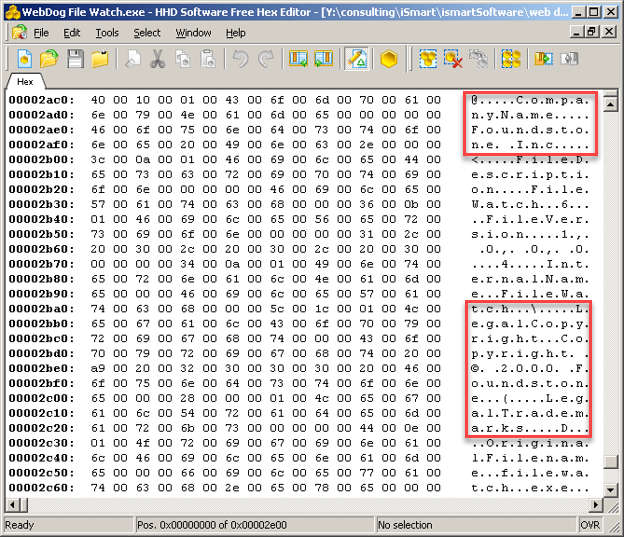

When a copyright notice is embedded in an executable program or is present in source code, I reach my expert opinion easily.

Sometimes all it takes is a hexadecimal editor to display this information.

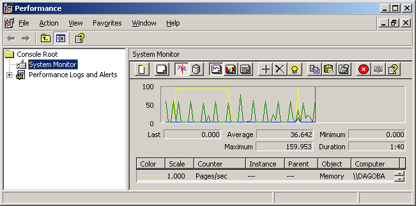

The image below shows that a company called Foundstone Inc. copyrighted a program called WebDog File Watch.exe in 2000.

Unfortunately for the defendant, this was proof that they had misappropriated the executable program from Foundstone.

A defendant misrepresented a Microsoft Windows program (an ActiveX control) as their own. By examining the executable image, I determined that it had been misappropriated from Microsoft.

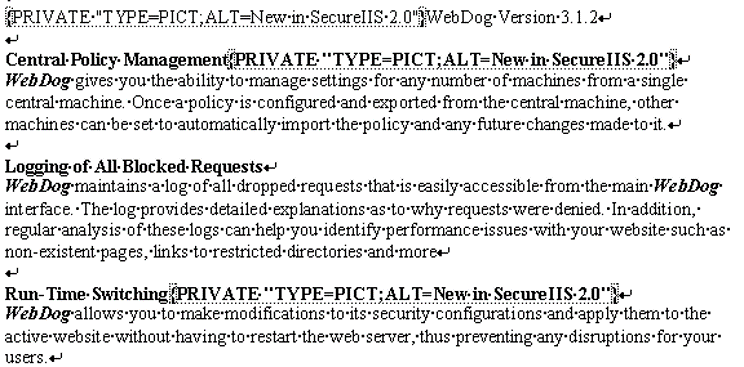

Microsoft Word – the Smoking Gun

A defendant included a Features and Benefits document in their CD. This Microsoft Word document was a modified version of the plaintiff’s Microsoft Word document that discussed a commercial product with exactly the same features as the infringing program. The defendant had left Microsoft Word’s revision marking on, so that an audit trail was present in the shipping product. My expert report stated conclusively that the defendant had misappropriated the software.

Sometimes My Task Is Not So Easy

The analysis necessary to form an opinion can be rather involved. The challenge that an expert faces when writing their report is often how to present their findings in a clear and concise manner to a non-technical judge and jury. Later in this article, I will describe a novel approach that can lead to a simple, very convincing report.

Equivalent Programs

A global edit is a text replacement made to all the files in a project. Making global edits to a copy of a project does not alter the fact that the project was copied. Merely changing the names of variables, classes and methods does not alter the meaning of a program. This means that performing global edits on source code results in an equivalent program. The same is true of literally translating a program from one computer language to another.

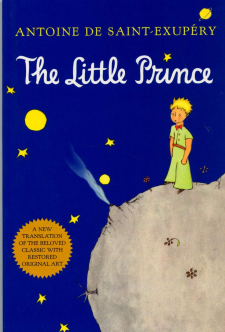

Le Petit Prince / The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint Exupéry is the world’s most translated book, excluding religious works. Originally published in English and French, this book has been translated into 361 languages. We will use this book as an example of how both types of copying could be accomplished. The same principles apply to software as intellectual property; note that we are not discussing copyright at this time.

Global Edits

In The Little Prince, the main character supposedly came from an asteroid known as B-612. The name of the asteroid could be changed throughout the book without affecting the book’s meaning. Therefore, a global edit that changed the name of the asteroid from B-612 to XYZ123 would mean that the resulting book would still be an equivalent copy of the first because the meaning of the story would not have changed.

Translations

The French version has more words because French is a grammatically longer language than English, but every passage in the English version has the same meaning as the equivalent passage in the French version. Both versions of this document are literal translations of each other because they have the same meaning. The actual words used are insignificant, so long as the meaning does not change. Thus, the English and French versions of the book are copies of each other, even though they are written in different languages.

The AFC Test

Since 1992 the gold standard for source code comparisons in copyright law has been the Abstraction-Filtration-Comparison (AFC) test. To apply this type of analysis, a certain degree of co-operation by both parties with the software expert is necessary. The AFC test requires that both parties allow their source code to analyzed by various software tools. Depending on the size of the software programs, this might require days, weeks or months. The computer that is used to perform the analysis must be specially prepared, and the results must be saved onto some form of storage media for further analysis before the expert can write their report.

The AFC test invariably results in a long and complex report filled with technical information. The abstract concepts in the report can be difficult to communicate to a non-technical judge and jury.

A Novel Approach for Detecting Copying

Comparing digital fingerprints can give compelling results and, if approached in the right way, can be a lot less work than the AFC test.

Let’s say that a music producer is accused of copying a song that was originally published as a vinyl record. Imagine that the complaint stated that the infringement was done in a way that the musical structure, lyrics and arrangement were substantially similar. An expert might attempt to perform an analysis of the structures, lyrics, and arrangements of the two recordings, and opine on the similarities. The problem with this approach is that the report would be rather technical, and there is a risk that the judge and jury might not understand the analysis. Additionally, there is always the risk that a jury might not come to an agreement.

To avoid these issues, the expert might show that the alleged copy was made from a specific vinyl record, not by analyzing the music, but by analyzing the noise (for example, cat scratches). The expert would have to exclude noise added in the production of the original recording (because all originals would have this or similar noise), and focus solely on the noise added to a particular vinyl record (for example, long, jagged cat claw scratches unique to one specific original record.)

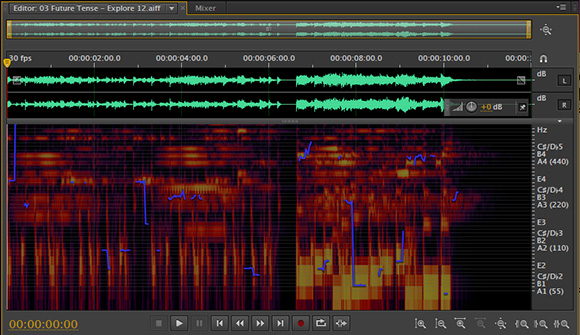

If, after the musical content is removed, the remaining noise closely matches the noise on the recording, then the degree of correspondence could be statistically computed. Noise could be compared based on the amplitude of each snap, crackle and pop. The energy spectral density of the noise could be displayed as a timeline, and the degree of correspondence accurately computed. This approach (comparing noise) would actually give a much better result than theoretical analysis of the music, and would be more convincing to a judge and jury.

To summarize, the approach described above compared the digital fingerprints of the noise in two recordings, instead of comparing the fingerprints of the actual recordings.

A Difficult Case Had an Unexpected Benefit

Recently, I was retained on a case that was particularly challenging because both parties refused to allow me to use any tools. Furthermore, the opposing party’s software to be examined was provided on a computer without internet access, and I could only print 100 pages of notes in total during a relatively short visit at the offices of their attorneys. However, necessity is the mother of invention, and I developed two novel approaches that allowed me to opine that there was clear evidence of inappropriate IP infringement.

I took a similar approach as described in the novel approach described above for this case. I would normally analyze input and output patterns, but the defendants chose to make more complete analysis impossible. In the limited time available to me and with only the most rudimentary software tools permitted I was unable to compare processing, object models, SQL tables and other standard aspects of software programs.

I focused instead on the ‘noise’, which in this case were unusual artifacts found in the software. Unfortunately for the defendants, the results of analyzing the software ‘noise’ were incontrovertible. The mathematical probability that the backbone of the defendant’s software would coincidentally have an identical noise fingerprint as the backbone of the plaintiff’s software was vanishingly small. The parties in this case settled at the 11th hour in the evening before trial.

Summary

Many techniques are available for a technology expert to employ when examining evidence. Out-of-the-box thinking can provide excellent results that are technically sound and present clearly to non-technical audiences. Experts who are skilled at writing Microsoft Office macros can provide tremendous value.