Published 1999-09-12.

Time to read: 6 minutes.

mentoring & advising collection.

I wrote this article 26 years ago. Much of it is still relevant.

Companies that develop technology in new market areas face risk from not applying the technology in a manner that is understood or usable by their targeted market–or they may face the risk that the technology is ahead of the market demand. The base technology may be sound, but a company that misses its market usually does not have a second chance.

Follow-on companies that take advantage of the learning experience of the now-defunct first company to market have a greater chance of success. This document discusses a time-tested approach that the author has applied to an Internet startup as a means of minimizing risk and broadening the number of participating partners while maintaining flexibility for future mergers and acquisitions in the industry.

Monolithic Corporations vs. Holding and Operating Companies

Innovative, technically based companies that develop discontinuous new paradigms expose themselves to several types of risk: market not ready, value proposition improperly articulated, market grows slower than expected, etc. Most of the risk lies with the customer-facing aspects of the business. The innovative technology and processes underlying and supporting the customer-facing business can often be repurposed into supporting other potentially viable customer-facing businesses.

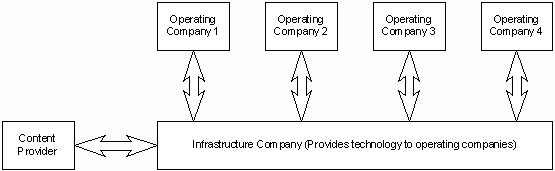

Separating the technology infrastructure developed by the company from the customer-facing business produces a group of related companies, as shown below. This diagram is modified from an actual diagram developed for a client:

In the diagram above, four possible operating companies are envisioned, all leasing their technology from the holding company. Each operating company has a different business model. The interface for each operating company to the infrastructure is common, however.

The valuation of the group of companies is frequently much greater than if all the assets and activities were held in one company. One reason for this is that risk (which depresses valuations) is partitioned into operating companies. Another reason is that the value of each company is tightly bound to its mission. Should a company be unprofitable, it might be replaced or shut down without affecting the other companies. By explicitly showing each company’s value, the value of the entire group of companies is more readily demonstrable. AT&T’s recent desire to split itself is an example of this, as is the historical example of the increased values of the Seven Sisters upon the breakup of Standard Oil in the last century.

The operations companies would pay for fixed and variable costs incurred by the infrastructure company, plus a one-time setup charge, plus a base cost per month. Any applicable royalties for content would be computed by the infrastructure company, but would be paid instead directly to a content provider. The infrastructure company would not be responsible for the content flowing through it (like telcos.) The motivation here is for the operating companies to assume all risk.

Infrastructure Company

The infrastructure company (actually a holding company) would develop and maintain functional components for the operating companies under an ASP model. Any development specific to one operating company’s needs would either be developed by the infrastructure company at arms length or by an outside company using the APIs published by the infrastructure company.

The infrastructure company would not need to build a brand and would not be exposed to market risk.

Operating Companies

Each operating company would have a different business plan, and would seek to build individual brands. Risk from customer-facing operations would be held solely by the individual operating companies.

Barriers to entry and time to market for successive operating companies would be less than for vertically integrated companies. Operating companies might compete against each other using different business models. Arms-length parties might launch customer-facing operating companies in competition to those launched by the original founders, but the founders would still benefit since they would own the infrastructure company that would provide products and services to all customer-facing companies.

Conclusion

Using technology holding companies to separate out the risk incurred by customer-facing ventures is not new. In general, however, Internet companies have not used this tried-and-true corporate strategy. Now that the dot-com bubble has burst, investors have a renewed interest in business fundamentals. One should expect to see more holding companies in the Internet marketplace as the business use of the Internet continues to mature.

Comments from Readers

From a CEO

We use development to create the many layers needed based on a common infrastructure and use operations to run it. The tricky part is how formal to make this structure and the chargebacks that could go with it.

Mike responds:

In the right circumstances, the improved focus and ability to manage risk that this corporate strategy provides would more than compensate for the extra overhead.

From a Business Development Manager

If you have a captive market of operating companies, other operating companies will not buy from the infrastructure company because they believe that the “well is poisoned”, and they would not get a competitive advantage from purchasing the infrastructure company’s products and services.

Mike responds

I agree that complete outsiders would not be likely to attempt to set up operating companies that compete with operating companies owned by the same people that own the infrastructure company. However, this would not be a problem for companies that want to break into a different market with a different business plan if the owners of the infrastructure company offered suitable non-compete guarantees. There would also be an opportunity for other companies to partner with the infrastructure company’s owners to develop competing companies that run on different business plans but address the same markets.

However, even if no outsiders ever use the infrastructure, it still serves its primary purpose: to protect the substantial intellectual property and capital assets that were developed and acquired by the owners of the infrastructure company.

From a senior software architect

I get the idea: instead of making an internal division of the company along responsibility lines (‘this group is responsible for productizing along these lines’), make the division completely explicit in the corporate structure.

There are probably many reasons for doing this. I can see three right away:

- A much more easily understood bonus / performance structure. One thing I absolutely hated in a previous company was that my profit sharing was based on the entire company. My project, the one that I ran, did amazingly well. The rest of the company did lousy. And my bonus suffered.

- It makes it easier to do things that are not necessarily fully in the interests of the other operating companies (which might be prevented in a single corporation).

- It simplifies the whole merger/acquisition/recombination thing.

The diagram is a lot like BEA/WebLogic and the people who build EJB-backed websites. There are lots of specialized little companies that use EJBs to build websites, and they go after small sectors of the market. So, they’re like operating companies, except BEA/WebLogic does not own them.

Question: What difference would it make whether BEA/WebLogic owns them or not? Unless the operating companies are meant to preclude other, external partners, the infrastructure brand could be significant.

Mike responds

I like the analogy to BEA. I would like to point out that BEA incorporated WebGain, which is a separate but closely related business. WebGain’s VisualCafé product line was acquired from Symantec, partly due to its close coupling with WebLogic. The WebGain example doesn’t completely fit in with the thrust of this article, since it is not an operating company that utilizes an infrastructure provided by BEA.

Regarding brand, I accept your comments with caution; when I worked as a regional manager of a Canadian distribution firm, our goal was to be invisible to end users–we only wanted to be known to our customers, the retailers. So it should be with infrastructure firms; their brand should remain within the industry that they serve. It is costly to build a brand, and the level of expenditure required to build the brand for the public would mean that marketing costs would become the infrastructure company’s largest expense. Good examples of pure infrastructure companies are Exodus and Digital Island.

About the author

Michael Slinn is a technical business strategist. He consults in the Internet Business to Business (B2B) and Business to Consumer (B2C) arenas and focuses on server-side architecture and technical/business strategy.

No longer can executives make high-level decisions without regard for technology and simply direct their technical staff to execute; the business strategy must be integrated with a technical strategy.

This is particularly true in Internet startups and business makeovers. Michael facilitates the development of a total business technology concept. Few people can sit in a technical / marketing / business discussion and contribute in all areas, but that is Michael’s unique strength.